It’s spring here in the US, so for many that means it’s time for the “big clean”. We dig into our closets, find a pile of tired clothes, and dump them at the Salvation Army or Goodwill. Maybe Oxfam if you’re in London.

You might think that your donations go to the back of the store and reappear on the racks. “I assume they go into the Goodwill stores,” Julie Stevens told us as she dropped off a donation at Goodwill in Dallas, Texas. “Things are sorted out, cleaned and put into the store,” she says. “But that’s just an assumption.”

Turns out, just a small percentage of your donations stay in the store, according to our guest Andrew Brooks. “It’s likely they’d be taken to a large processing plant where they will be sorted into different categories and they will end up being sent overseas and recycled.”

Donated clothes are a big business in Africa, where textile importers are most interested in warm weather clothes, such as t-shirts, shorts and jeans. Bales make their way to markets in developing nations where they are purchased by vendors who re-sell the clothes, piece by piece.

Brooks’ new book, Clothing Poverty – The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-hand Clothes describes a multi-billion dollar industry, fraught with complexity and even deceit.

CHARITIES AND COMMERCIAL COLLECTORS

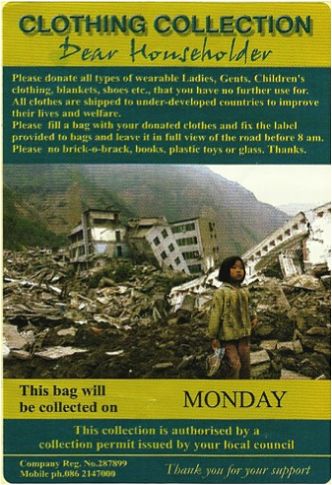

Given the profits that can be made, it’s not surprising that, along with charities, commercial collectors have gotten into the second-hand clothing market. Some of these commercial collectors are legitimate and some are not. For example, some for-profit companies use images to make it look like they are donating clothes to the poor.

Brooks received this flyer from a commercial company in England, which he says used a stock image of an earthquake:

You might think that this flyer promises that the company will give away clothes to earthquake survivors, however, Brooks says the company is not a registered charity and will likely sell clothing donations for profit.

The use of charitable images like this one by commercial collectors is “relatively prevalent” according to Brooks. “They might put teddy bears, they might put a picture of a child, they might put smiley faces, recycling emblems, first aid crosses; these sorts of images on their collection leaflets,” he says. However, he acknowledges, “It’s difficult to map and understand them because no one is really out there, collecting data on these organizations.”

SECOND-HAND CLOTHES: A GOOD THING?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

But this problem of illicit trading of donated clothing is only a small part of a much larger problem, says Brooks. He argues the entire system of charitable clothing donations to needy countries is flawed. “I have spoken to hundreds of people in Africa,” he says. “They don’t want to wear your used clothing. If they are given a choice, no one would choose to wear an old t-shirt from here, no one would choose to buy second-hand underwear, which is very commonplace in the markets. If you think that this is a really good thing, I think that’s strange. It’s a strange way of looking at the world.”

Brooks says rather than thinking we are solving problems by donating unwanted clothes, we need to focus on political and economic initiatives that will revive Africa’s once-thriving textile industry. “This is something that many African countries did initially; they set up clothing factories, they produced clothes, which were consumed and bought locally.”

He says today, African nations cannot compete with countries like China and South Korea, which successfully put up trade barriers to protect their own fledgling textile industries. Brooks says African industries need to be fostered in the same way, so that Africans no longer rely on our cast-off clothing but instead are producing and buying their own new clothing.

If you still feel you want to donate clothes to charity, Brooks’ advises you to find one that will resell your clothing only locally but he admits that it is often hard to figure out where donations will actually end up.

Do you think the second-hand clothing trade is a general good or harmful to local economies? Have you received flyers at your door appealing for second-hand clothing? Do you know if they were for-profit companies or charities? Please take a shot of flyers you’ve received and send them to us.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Clothing Poverty on Amazon

Andrew Brooks’ website

Andrew Brooks on Twitter

Battle Erupts in California over Clothes Donation Bins

Clothing Bin Donations Don’t Always Reach Needy

NOTE: After we posted this podcast, we heard from Ian Falkingham, who manages Frip Ethique, Oxfam’s second-hand clothing project in Dakar, Senegal. Falkingham praised Brooks’ book as “excellent” and “timely” but wanted to clarify two points:

First, Falkingham said that Oxfam does not send winter clothes to Africa. “We export a grade of clothing sorted so it’s appropriate to the markets into which we are selling,” he told us in a Skype interview. He clarified that Oxfam sells short-sleeved shirts, cotton tops and “items that people actually want” to Frip Ethique in Senegal and a commercial company in Ghana. Donations of heavy coats, woolens and fleece are exported to regions like Eastern Europe, where they are sold for a “premium price because people want those kind of goods.”

Secondly, Brooks did much of his reporting for Clothing Poverty in Mozambique, where he described clothing bales as sometimes containing stained or moldy items. Falkingham contends that all of the clothes Oxfam sells undergo quality control processes. Frip also does a final sorting to remove any irrelevant or poor-quality items that might have slipped through. Referring to the end products at Frip, he said, “If you buy a bale of jeans from us or a bale of cotton blouses, we should have been able to pull out anything which has holes in it or isn’t fit for standard.”